Why I Am Not A Teacher

Ludwig Wittgenstein, of modern philosophers perhaps the most sainted, served time as a schoolteacher. I am not surprised. I am also not surprised that he resigned his position after hitting an eleven-year-old boy in the head. I tried to remind myself of that at least once a week throughout this past year, and not so I could fancy myself superior to Wittgenstein. Rather, I wanted to remember that what I had undertaken was by no means as safe or as simple as redirecting the course of Western thought.

from 'Getting Schooled' by Garret Keizer (Harper's Magazine)

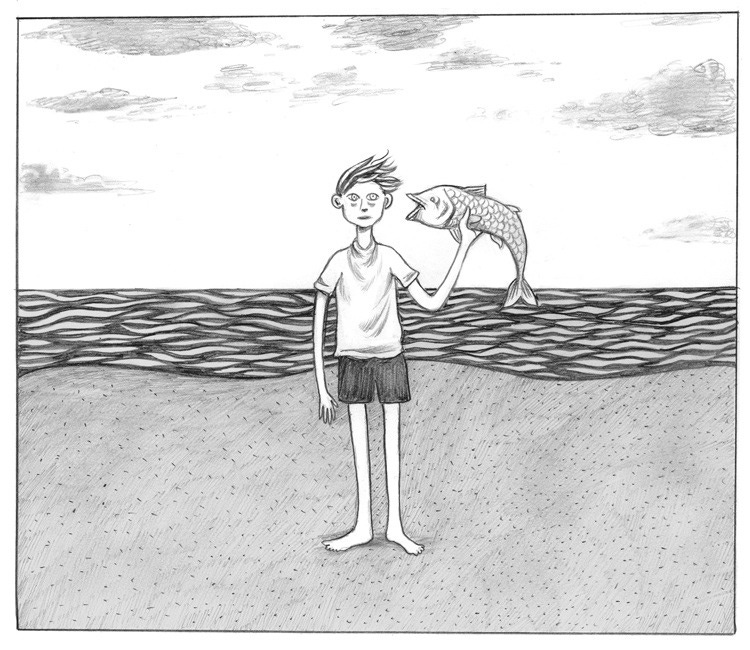

Lilli Carré, panel from "Too Hot to Sleep", via 50 Watts

Whenever I don't know what to do for a job, I think about going to teaching college. This impulse gets me every few years; it's like a fever that must be starved out. My mother has taught in high schools for decades, and our house was often filled with teachers. They would park their cars in the paddock and infiltrate the house and the garden, especially at the end of the year after prize-giving. "Call me Owen!" I remember the deputy principal slurring, as he folded up into a collapsing deck chair on the lawn.

I would not be a good teacher. I am frightened of teenagers. If I have to talk to one, I revert back to a high school student myself - miserable, awkward beyond belief, head too small for my body, a human mouse. It was a lifetime ago and my memory of being a high-schooler is still like a fresh bruise on the ribs. But this doesn't stop me, every few years, from hacking out plans to become a teacher or a tutor. Growing up with a house full of teachers made me see that they were just humans, mostly ordinary humans with voices that projected particularly well across a room, and when I'm having one of these episodes, my brain fills with hot air and I think, "I could do that."

But I know, rationally, that I couldn't. I remind myself that even though my teachers were just humans, they also had an inner steel, a fortitude that enabled them to bear "the relentless experience of finitude that is teaching", as Garret Keizer writes in his essay Getting Schooled [PDF]. "There is nothing like a school to make one aware of mortality. ... The angelus that rings - not three times a day, as in a monastery, but every forty-five minutes - remorselessly drives home one's sense of limited time on the earth, of diminishing chances to do the work and get it right." Whenever I think of my primary school teachers, and I think of them oddly often - Miss Knight, Mrs Muir, Mrs Lile, even Miss Irvine, who could be terrifying, even Trunchbullian, but was often hilarious and kind - I imagine them in a kind of heaven. I imagine them in vast sunny gardens, trailed by cats, or reclining in corduroy armchairs beside shelves of books, at rest.

At my high school, which was very small, if kids sensed weakness in a teacher - any degree of shyness, lack of confidence, a short fuse - they would eat them alive. My form room teacher, Mr Earl, not only had a gentle, earnest manner, but he wore shorts all year round, with leather sandals and long scalloped socks. And not only this, but he had a glass eye. (It's only now, writing this, that I realise I don't know how Mr Earl lost his eye. His glass eye was so much a part of him, so much a part of how kids responded to him, that he might as well have been born with it.) The eye was shark bait. The goal was to taunt him to breaking point, at which he would slam his hands down on his desk and bellow in jowl-wobbling fury. And the kids would laugh their heads off. My brother has a friend, the gentlest, most softly-spoken, self-effacing young man I think I've ever met, who has been teaching for a year in Porirua, and when I asked him about it recently I swear I saw the shine of tears in his eyes. "It's very hard. The kids are a lot of hard work," he said. My brother confirms that from what his friend has told him, yes, he is being eaten alive.

Friends by Laura Gee

My mother taught Japanese at my high school. Through the haze of my embarrassment, she always seemed canny and thick-skinned, but even she lost control sometimes. Once, in Japanese class, to widen our culinary experiences, she brought us all some silken tofu to try. But - my god! - the tofu, which had been in the freezer, had not defrosted properly. There were chunks of ice in it. At this discovery - as well as the inherent awfulness of uncooked silken tofu - the class disintegrated into mayhem. A group of my classmates burst out of the room and started running up and down the corridor, lobbing tofu at each other. I can still remember the shrieks of my mother in the corridor, failing to get things under control, until mercifully the bell rang and everyone just left anyway, clods of tofu underfoot.

My mother had a caravan, out in a paddock, which she'd converted into an office. She went out there most weeknights or early mornings, with the dog and a cup of tea, to do her marking on the fold-out table. The bunk beds were stuffed with filing boxes and the wardrobe with rolled-up classroom posters. Sometimes I went out to sit on the floor and read while she was marking. She'd be cringeing over the papers. "Oh, for GOD'S SAKE, Jeremy." "OH HELL, ERIN." "OH what have you DONE, LEEZA." I'd always wanted to believe that teachers must love what they do - they had to; why else would they do it; were they insane? - but small things like this, as well as the many beleaguered conversations I overheard on the phone or at staff parties or on the main street while with my mother, coloured the way I saw teaching. At high school I realised that most of the teachers there disliked their work, or at least found it incredibly hard and unforgiving - the hours too long, the pay low, the students more brainless by the year. I once overheard my mother say to an old colleague, who had left teaching: "The teaching has gone from your face. It's lifted away. You look well again."

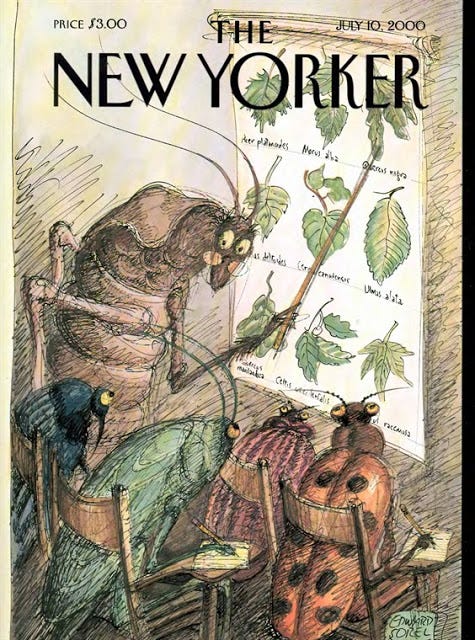

Edward Sorel (via Animalarium)

The word pedagogue derives from a Greek word for a type of slave who led children to school. This detail is included in the essay by Keizer, who gives an account of his decades of teaching and argues that it is unfair to assume that a teacher works out of love for their profession. While he isn't suggesting that teachers are like slaves, he says: "I am inclined to distrust people who expect me to work for love, or who need a sentimental mythology to gloss over the impossibilities of my job and the daily injustices it lays bare." The only teaching I've ever done was teaching piano to six- and seven-year-olds, one of whom farted so relentlessly throughout lessons that it put me off primary schoolers for good, so I have no real understanding of what it feels like - what it might do to your state of mind - to grapple with those impossibilities and injustices, and to field the assumptions that you do it for love.

In the last week or so, I've been marking a couple of MA folios, and I like it. I like it a lot. This is highly dangerous. When this happens, I have to use my special tool. It's a children's book. It's the kind of book a child would only read in a classroom because they had to. There is a picture of me on the cover of the book.

At a publishing company where I was once an editor, I was photographed playing the role of a teacher for this book. I had to pretend to be standing at a whiteboard pointing out rules for classroom behaviour. (It's a book about "being a good citizen".) Progressively, page by page, my facial expression morphs from harmlessly friendly into gormless, Father Dougal-like bewilderment. I don't know what I'm doing. The kids who had been hired to play the role of the students knew it, too. They sat on the mat in their diversely coloured t-shirts and wouldn't smile, like a bunch of mini Holden Caulfields: what a phoney. But for all it grieves me to look at these pictures, I've found it to be a highly effective teaching dissuasion device.

(No, pictures from the book can never be published here. Sorry.)